I can still see Flutie’s pass fluttering through the rainy night sky in Miami. Gordon’s kick soar up in the air in South Bend, gloriously fading left through the goal posts. Ryan’s across-the-body strike in Blacksburg to stun the Hokies. My great-grandfather, grandfather and father’s all experienced these moments as well. Moments when loyalty, devotion and yearning unknowingly flipped to ecstasy and joy. What if, what if us? Please let them contend for something big, someday. Please.

In 1919 my grandfather Jerome attended his first Boston College football game with his father, John B. Doyle, and his brother Dick. BC took on then powerhouse Yale in New Haven, Conn., and trailing 3-2 late in the game, star halfback Jimmy Fitzpatrick booted a 48-yard drop kick to give the Eagles a stunning upset. J.B., as he was known, was devoted to his alma mater, and he brought Jerome and Dick every year to see BC take on archrival Holy Cross in bloody games where fistfights ensued.

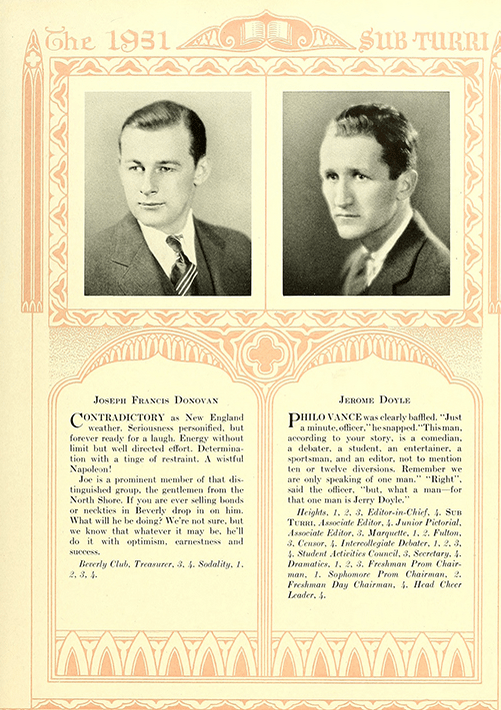

After graduating BC in 1931, and a long distinguished career at the FBI and Wall Street law firm Cahill & Gordon, Jerome and the rest of my New York-Irish family were sucker punched by sudden death of my grandmother Gertrude, in 1972. A couple of years later, he fled his Larchmont, New York home for the quiet Cape Cod hamlet of Osterville. There he became a pro-bono defender at the Barnstable County Courthouse and signed up for BC season football tickets.

As a kid, my brother, dad and I would putter from the Cape in his old Mercedes to Big East games. Below his plaid fedora, he would squint down at the hard astroturf field on crisp, sparkling autumn New England afternoons. He would force his hands together trying to clap, but his pinky and ring fingers crumpled in his palms – yellowed and balled up from decades of smoking unfiltered Lucky’s. He would wrap his frail body in a big tan coat, and a blanket when it was colder. My jean jacket and mesh hat clad father would always sit next to him, in his ear about some player or coach. Periodically, my dad would deafeningly scream out at the game.

Jerome bought these seats at the 50-yard line, 22 rows up in the mid-70s when BC hardly mattered. But then a few years later, Flutie’s pass put Boston College on the map – football took a giant leap and applications surged. BC went from being a small New England institution steeped in tradition to a national, prominent university.

After his death in 1989, my father took over the tickets and watched the price climb to $50 a seat. Nearly a decade ago, begrudgingly and reluctantly, Boston College mandated 7,400 of its season ticket holders to “donate” $1,000 to $500 to keep their seats near the 50-yard line. The school was the last in the Atlantic Coast Conference to require giving for the best seats because the cost of funding scholarships, new facilities and team expenses are just as jaw-droppingly expensive as BC’s yearly price tag for tuition, room and board, now approaching $60,000. For years big-time programs in the South have issued similar mandates, but the heavy cost of big-time college sports now reaches buttoned-up BC and its medium-sized stadium in Chestnut Hill.

But BC is different. Deeply Jesuit Catholic, chock-full of well-off kids primarily from the Northeast, charging New England old timers and families like mine that have endured many a bad BC teams was certainly a curious move.

As this all came down during the Frank Spaziani era, a particularly listless stretch in which our recruiting vanished and teams were pancake flat of emotion and ability. So the “donation” felt like a waste to our family, which resides outside Washington, DC. We passed on the donation and moved down to the 10-yard line. Still fine seats, with an excellent view I felt a bit lost at my first game. I kept looking down toward the 50.

As a freshman, I watched David Gordon’s fading 41-yard field goal fall through the uprights to beat then No. 1 Notre Dame. BC’s campus exploded even though the game was in South Bend with students running wild and tearing down our own goal post and leaning one on Gordon’s run-down townhouse, in BC’s beloved mods. We ended up #13 in the nation that year. As I neared graduation, the team declined and then precipitously plummeted into a gambling scandal. Unable to come or to unload the tickets, my dad would send me my grandfather’s seats. I’d sit there with a friend – away from the ruckus of the student section – and the memories would again wash in, somehow overtaking the terribleness on the scoreboard.

Life is expensive. As a father of three (9- and 11-year-old stepsons, Matteo and Luca, and our daughter, Romy, 4, who was named after Jerome) living in a DC suburb I understand this: bills, mortgage, nanny, more bills, camps, birthday parties and year-round soccer teams with professional coaches. But something is getting lost when a tier-two football program is trying to get a die-hard fan to pay nearly $2,000 a seat a season. That’s twice as much as most NFL tickets.

Yes, my family has a deep, nearly unprecedented relationship with Boston College and its football team. I don’t think we deserve anything for more than 100 years of loyalty. But charging so much for tickets cheapens loyalty and devotion regardless of who you are. It makes the game and being a fan about what’s in your pocket or bank account when it should be about how much you care. It should be about your willingness to sit there in a cold rain, not your ability to write a check with many zeros.

Sports is a great equalizer for any fan of any team. A 40-year-old dad with plenty of budget or an 18-year-old freshmen with 10 pennies shouldn’t have to make economic decisions about their loyalty. My dad has held onto those seats all these years after my grandfather’s death because of the memories of sitting there altogether reveling in the moment.

It’s been many years since we went together. We went up for a game before I got married. I think we played Notre Dame. I don’t really remember. We sat there together under the lights. There it’s hard to say what loyalty costs. It’s incalculable and any attempt to charge too much simply devalues that feeling and experience.

I wonder what my grandfather, a man of who successfully sunk a plan to install parking meters at the Barnstable County courthouse as a public defender in the twilight of his career, would have said about the soaring cost to go to a Boston College football game. I’m certain he would have uttered his signature curt line, “Is that so?” and rolled his eyes.

I haven’t brought my kids to Boston for a game yet, but I did bring them to a University of Maryland-Boston College game a few years ago. Andre Williams ran wild, and somehow led an improbable field goal winning drive at the end of the game. Ultimately, those are the moments that matter. The moments you remember sharing with your kids, father and grandfather. I want more of them and I don’t want to overpay for them.

This is poignant. A beautifully written piece that the Boston College “money makers” need to read. Life is about living what you love, with passion, not about the big bucks. Tim Doyle has his finger on the right pulse.

So true..BC has lost its’s identity to big bucks and greed!

It’s not “chalk full”, it’s “chock-full”.

You’re right! Thanks for the catch.